By Gerry Madigan

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted for the generous help and time of many people who allowed me to use their photographs, peruse their scrapbooks and archives, and even mailed me valuable leads and content! All these have proved invaluable to compiling and writing this article.

I truly thank the following for their most generous help and encouragement:

- Community of Country Harbour:

- Robert and Gina Walsh, Cross Roads Country Harbour, interview and permission to use pictures and archives

- Norma Cooke, Isaacs Harbour, her many letters, comments and use of her archives

- Jane Dort, Cross Roads Country Harbour, interview, review and confirmation of information, and additional leads

- Beulah (Fenton) Myers, Country Harbour Mines, interview as witness to the events of 1944

- Wilmer Hodgson, Country Harbour Mines, interview as witness to the events of 1944 and his special memories of the walk through the woods

- Mickey (Fenton) Harpell, Halifax, interview as witness to the events of 1944 and her personal story of the events of the forced landing March 1944

Associations:

- Chis Charland, Aircraft Research, National Air Force Museum of Canada, Trenton, Ontario

- Chris Larsen Air Historian, Greenwood, Nova Scotia

- Chris Larsen (no relation), Historian Pennfield Parish Military Historical Society, Pennfield, New Brunswick

- Mark Peapell, Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum, Halifax, Nova Scotia

A brush with history

Country Harbour, once considered as a possible site for Nova Scotia’s capital, is blessed with a deep water port, one hundred miles nearer European markets, an important strategic location in the days of sail and rail. Country Harbour is a place often brushed by history.

Country Harbour’s deeply interesting history would be brushed with many events, some even in the very early days of flying. On 25 June 1930, Captain Charles E. Kingsford-Smith began an epic journey from Portmarnock Beach, Ireland to Roosevelt Field, Long Island. It was amongst the first trans-Atlantic flights to be attempted. Captain Charles E. Kingsford-Smith with a crew of three in a Fokker Tri-motor called the Southern Cross set off in the hope of success of the venture.

But Kingsford-Smith’s journey almost ended in disaster. He became lost in the mid-Atlantic. He was only saved from certain death by radio direction to Cape Race, Newfoundland, landing with only fumes remaining in his fuel tanks. His journey continued on the 26th June and his progress was closely followed given his brush with death.

Kingsford-Smith reported “Found clear patch and am down 1000 feet. Now passing County Harbor, Nova Scotia, on our left.”[1] The newspapers of the day said “It fell to the villagers of County Harbor, 100 miles from Halifax, on the Now Scotian coast, to be the first to see the plane. The Southern Cross was passing County Harbor, N. S., about 109 miles east of Halifax at 10 a. m. EST, today, according to a message picked up by the coast guard radio station here.”[2]

But in 1930, the skies over County Harbour, actually Country Harbour, were kissed by the brush of history in the coming age of air travel and air power. A war too was just on the horizon looking toward Europe! Country Harbour would be kissed in other ways some 14 years later, only deeper in its interior at Cross Roads Country Harbour and Country Harbour Mines.

The Crash 1944[3]

Fourteen years after Kingsford-Smith’s flight by Country Harbour, another aircraft incident would occur one Saturday afternoon, only this one on 4 March 1944 at the height of the Second World War. A plane out of RCAF Station Dartmouth was returning from an operational anti-submarine patrol and was in-bound to home base.

It came to be in certain distress when passing by Country Harbour. It was about three o’clock that afternoon when it crossed the Nova Scotian shore at some unknown point. The aircraft and crew were lost. They radioed their plight to the Aircraft Detection of Eastern Air Command’s Flying Control Unit.

Flying Control immediately alerted a number of observers in the district of Country Harbour where they believed the aircraft to be flying. The observers subsequently filed two reports from the vicinity of Goldboro, NS very shortly after receiving that warning. They confirmed that the aircraft was indeed seen flying over. This important information was most likely conveyed to the aircrew who from which were able to fix their location, to track their course and to report their progress from that point on.

But knowing their location did not resolve their true problem and difficulty. They were not out of the woods, in fact, were still in deep trouble. They were wandering up the river trying to find a suitable location for a forced landing.

A landing was considered at Isaacs Harbour but that ice appeared unsafe. So they simply flew on looking for better options. They maintained radio contact along the way. But time was running out. They advised Eastern Air Command Flying Control that they were about to make a forced landing on the surface of a snow covered lake, which they identified as Stewart Lake as their probable location.

Eastern Air Command Flying Control reacted quickly. An aircraft was dispatched from Dartmouth and flew to the vicinity where it successfully located the four men, but not on Stewart Lake as thought! In fact they were on a small lake according to later reports some six miles distant.

The aircraft had actually crashed on Archibald Big Lake just to the north and east of Cross Roads Country Harbour but its true location was not yet known. Their probable location was once again misidentified this time by the rescue plane as Tom Mann Lake.

The rescue aircraft was able to drop supplies to the stranded men. It was lucky that none of the men were injured in the forced landing for ski-equipped aircraft were unavailable as they were deployed elsewhere. The crew was to remain on the lake for a number of days! A speedy recovery was improbable.

Rescue 1944 – The Local Coordination Centre[4]

The question would now become how to rescue these stranded men? The answer was sought through local knowledge. Flying Control contacted an ADC Observer at Goldboro, a Mr. Davidson, and Constable Osborne of the RCMP at nearby Sherbrooke for their assistance.

Flying Control told Mr. Davidson, and Constable Osborne where the aircraft likely was. They wanted to know the ways and means of getting in to the lake by surface travel.

Their call initiated a great effort that had to be coordinated. That task fell to Miss Laurie Sears, the Chief Telephone Operator at Sherbrooke, NS. Miss Sears quickly used her own initiative.

Miss Sears called what help was at hand on the very first call from the reporting centre that a plane was in trouble over her area. She alerted several observers who she knew to be in the path of the laboring aircraft. Their contacts and reports were immediately passed through her to the reporting centre.

Miss Sears would subsequently become the clearing house and action centre for the rescue and its coordination throughout what turned out to be a two week ordeal.[4] It was said that “Miss Sears practically took over and handled the alerting, the securing and passing of information herself until the men were finally rescued.”

The Aircraft Detection Corps Observers assessed her actions to have been extraordinary. Miss Sear’s contributions in the reporting and subsequent rescue of the crew of an aircraft that crash landed on the lake near Country Harbor Mines, N.S. in 1944 were highly praised. She was credited with a kudo: the successful rescue “should go to Miss Laurie Sears the Chief Telephone Operator at Sherbrooke, NS.”

The rescue truly begins – The Community of Country Harbour Comes together

But that was the work behind the scenes. What happened on the ground was truly extraordinary, largely unreported, and was Homeric in all its aspects.

Despite the fact that the crew of the plane was in direct contact with its operation centre reporting their position throughout its ordeal, they had little idea where they were, exactly. The problem lay in the incorrect identification of their true location. They were not on Stewart Lake but in fact on Archibald Big Lake.[6] Finding them took a considerable effort.

The plane`s track was well known. It was spotted in a number of locations particularly at Isaacs Harbour and Goldboro but it had proceed inland, in a westerly direction, upriver into what was then, the wilds of Nova Scotia. It was lastly spotted over the home of Obie Fenton where the plane was observed to be in trouble by time it reached a field near his home. So there was only a general idea of where the lost crew was.

A newspaper article from 6 March 1944 summarizes events in a nutshell. It reported that a twin engine bomber had a forced landing at Forest Lake, Guysborough County. It goes on to say that “A local rescue party left for the crash site at three PM that Saturday afternoon. The aircrew was found and the party returned to the settlement around 10PM that night.” Frank Newman was named as the aircraft captain of the downed plane. The local RCMP were brought in from Sherbrooke to coordinate in the rescue.[7] It seemed simple enough on paper but it wasn’t.

It wasn’t to be that simple for Obie Fenton and his crew of volunteers. Three different locations were given in various reports as to the location of the downed crew ranging from Forest Lake District, Stewart Lake, to Tom Mann Lake. This indicated that the crew’s location was anything but certain despite the reports from ADC. They still would have to be found by Obie Fenton and his team. This was the task that lay ahead for the people from Cross Roads Country Harbour and Country Harbour Mines.

The winter of 1943-44 was bitter and cold with a deep snowpack. Snow lay heavily on the fields and woods around the area that March 1944. The ice was thick on the lakes everywhere in the county. There were no signs anywhere of a spring melt or break up.

Country Harbour was locked in the harshness of winter’s embrace.

A thick crust of ice was embedded in the snow pack. That crust would soon prove to be an obstacle and impede movement and the speed of recovery. The coming rescue of the crew stuck on Archibald Big Lake was neither swift nor expeditious. In fact it was laborious.[8] But in the early afternoon Obie and Lloyd Fenton working away sawing logs had no idea of that or what was soon coming their way.

Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Beulah (Fenton) Myers’ Big Scare:[9]

The first signs of the pending adventure came from the observations of two young girls playing in a field. Mickey (Fenton) Harpell recounts that her older sisters Marion (Fenton) Mason and Gladys (Fenton) Harris, were out coasting as children often do on a winter’s afternoon.

Here they heard strange sounds of an engine overhead. It appeared to them that an aircraft was in some distress. The engines were running rough and may have been backfiring. But the changes in engine noise may have suggested another problem, the aircraft was likely running short of fuel and had to get down quickly.

Mickey said her sisters saw that both wheels were down and were very concerned of an impending crash. The young girls quickly made for the shelter of the trees. The plane passed over them, going on out of sight for at least three more miles before finally coming to rest on Archibald Big Lake.[10]

Mickey clearly recalls her father’s warning to his children at the time, “‘You knew when the wheels were down, the plane was going to land or crash … Dad had told us so’, so the children said.” The shelter of the tree appeared to be the quickest way to safety and out of the path and the danger of the descending aircraft for these young girls but the plane flew on disappearing from sight.

Yet there was still more excitement later that day. Another aircraft flew over but much later in the afternoon. Here the two younger sisters, Mickey and Beulah, were also out playing on the field with a number of friends and again with their older sisters Marion and Gladys.

This time a plane circled the field where they group were coasting, and they heard a voice speak. Someone in the aircraft was talking to them over a loud speaker giving them directions to a lake. This upset Mickey, Beulah and the others greatly.

Mickey remembers climbing on the fence calling to her father and his nephew Lloyd, who were working nearby, “Daddy come and get me!” All four girls and friends ran for home but not before seeing a kit bag dropped from the aircraft before doing so!

Apart from the engine noise, the voice from the loud speaker, and the sounds emanating over the engines that probably sounded like the voice of doom, they were more upset by the fact that they just had been bombarded with kit bags from the air by their own air force!

The kit bag actually fell not too far from where the Obie and Lloyd were sawing wood. Obie and Lloyd retrieved the package. Obie cautioned Lloyd about opening the package. There was a war on. They were very suspicious of anything strange and proceeded cautiously! They took the package to Mickey’s Uncle Hadley’s home where it was examined it in greater detail. Inside the kit bag were directions to the crash site, rations, a first aid kit, a hatchet, and sheathed knife.

They now had firm proof that an aircraft was in distress and its probable location.[11] The directions given by the RCAF were in the direction of Tom Mann Lake. The first location that was given was known to be wrong and was corrected from Stewart Lake some 10 km further distant from the forced landing site. But it was still directions to the wrong location!

The ground search for the plane and crew soon got underway that very afternoon. Obie and Lloyd Fenton organized a team. They and Wilfred Langley, Edward Kenneth, Mac Martin, Lawrence Hallett, Wilmer Hodgson and William Janes were amongst the first to pursue the rescue.

They faced a daunting task. There were no ploughed roads to the crash site, not even a beaten path where they eventually would have to go. The men had to make their way through deep snow but they were walking to the wrong Lake!

Wilmer’s memory of the walk through the woods[12]

Wilmer Hodgson remembers that walk well. He is now 91 years old and still lives in Country Harbour Mines. His story is enlightening. It was a very heavy winter according to Wilmer’s recollection. He recalls heading out with Obie Fenton and others at around mid-afternoon with nothing but the clothes on their back. They had a horse with them.

They faced a daunting task as there were no ploughed roads to the crash site. Wilmer’s recollection of the entry to the lake was from the Highway 316 approach out over the steep hill first to Tom Mann Lake thence to Archibald Big Lake. That was a very steep ascent that added greatly to their burden. The men made their way through deep snow; snow so deep that the horse got stuck and finally gave up in exhaustion. The men pressed on alone.

Wilmer recalls an aircraft constantly overhead. It assisted the team in the pursuit of finding the downed aircraft. The rescue plane maintained an orbiting station overhead, pointing/flying and guiding them in the general direction of the downed aircraft as long as possible. But the sunlight waned and it got dark. At some point it could no longer maintain its orbiting station. The team’s progress slowed, as they made their way through deep snow in the dark.

Carrying lanterns, they made their way and continued the rescue attempt throughout the night pushing on to the other lake. Their perseverance, determination, and hope was not misplaced.

The rescuers finally arrived at the crash site around 9PM. It was pitch dark at the time. Wilmer saw the broken trees at a point on the lake where the plane made contact with the wood line leading to the lake and followed it. There they saw skid marks on the lake leading to its far end.

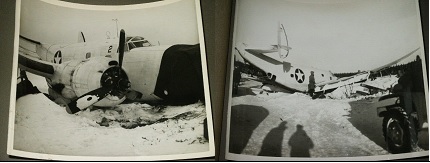

The aircraft was finally located! One of the wings appeared to be broken off as it lay at the lower end of the lake. The aircraft otherwise appeared to be in pretty good shape! It was not a catastrophic crash. More importantly the crew was alive!

There on Archibald Big Lake, from the evidence of tree damage, the skid marks, and the scrape on the lake, Wilmer, Obie and the others found the plane and its crew in a mound of snow at the far end about 300 feet from shore. But it was a clear indication of their close encounter was almost a total disaster.

The crew were outside of the aircraft. Wilmer recalled that they appeared in good shape, well supplied and were already under canvass with a fire going. None of the crew were injured by this encounter, they were simply waiting rescue.

The rescue team soon organized their safe removal. They were soon on their way out of the woods to be housed on arrival at Country Harbour Mines in the warmth of the homes of Mrs. Eliza Haynes and Mrs. Garfield Hodgson.

Mickey (Fenton) Harpell also remembers her father’s recollection of the rescue team on his return from the Archibald Big Lake rescue. The crew must have certainly been grateful for the community’s efforts. Mickey recalls “I remember Dad coming home after finding where the plane had crashed. He had tins of bully beef from the guys on the plane.” They were very well supplied indeed!

The crew was glad to be finally rescued, and in contact with the outside world. But they were about to embark on another great adventure– the repair, salvage, and extraction of their aircraft from the lake!

What the scene may have looked like

Coincidentally one US aircrew did encountered a similar problem in Newfoundland the prior year. Their story gives us an appreciation of the circumstances and difficulties of the day.

A Ventura Bomber operating out of NAS Argentia was on a routine anti-submarine patrol 27 February 1943. They encountered engine problems and had to make forced landing, damaging a wing and losing a wheel at Cape Bay Newfoundland.[13]

The crash record states that a PV-3 Ventura was returning from an operational flight. The weather suddenly closed in and the pilot was ordered to an alternate airfield. It was a brutal storm. The pilot flew on instruments for 3 hrs in a blinding snow storm. There were no navigational aids to guide him.

Captain E.H. Roberds, pilot in command, who tried valiantly to find an opening in the storm. When one was finally found, a spot in some marshland, he put down with only 15 minutes of fuel remaining in his tanks. Like the Archibald Big Lake forced landing, Roberds lost a wheel towards the end of his landing run. The PV-3 Ventura broke through a crust of ice, forcing his wheel to retract into the wells.

Captain E.H. Roberds had little choice or alternatives. His forced landing was very indicative of the dangers of operations of the day. The storm had closed all airports in the area. That attests to the very real and present danger facing all aircrews who partook of what was considered “routine” patrols.

This is what Captain E.H. Roberds’ crash looked like and what was most likely found at the crash on Archibald Big Lake just one year later.

Salvage and repair 1944

RCAF authorities must have been on site soon at some point to assess if the plane was salvageable. A decision was eventually made to repair the aircraft in the field. Those repairs on Archibald Big Lake took the better part of two weeks. Authorities brought in a replacement wing on a six-wheeled truck to effect the repairs from Halifax through to Antigonish and finally onto Country Harbor Mines.[14]

Patsy Fenton recalled the six wheeled truck coming in from Antigonish with a replacement wing for the repair.[15] The journey from Halifax through to Antigonish to Country Harbour would have been epic in its day. The roads were unpaved, and apart from the snow and the road clearing, the journey through the 316 from Antigonish to Country Harbour would have been tortuous, bone jarring, and slow. But the journey was essential given the importance of the wing.[16] The six wheeled truck finally arrived and hauled the replacement wing as far as Murray Hodgson’s home.[17]

But getting the wing to Country Harbour Mines was the least of the difficulties. The weather was problematic and had to be contended with. You would not be able to move for three or four days after a snow fall if the weather turned for the worst. Nothing would move in or be able to get out![18] Also it was March, a thaw could happen at any time. So there was an urgency in getting a replacement wing out to Archibald Big Lake and repairing that plane.

Getting the wing to the lake proved to be a challenge. There was no viable road into Archibald Big Lake. The initial plan was to truck it to the lake after a purpose built road was constructed. A woods road was constructed through to the site of the crash, which took time.[19]

MacRitchie Hayne recalled that bulldozers cut a road through the woods. He remembered there was a lot of snow with a crust build up that often halted and impeded progress. There was more than one metre of snow on the ground. To add to the difficulties, the incline to the lake proved impossible for the six-wheeled truck to climb. It just couldn’t make it up the hill![20]

The plan to use the six-wheeled truck was revised. The wing would be transported to the lake – old school – by a team of horses. MacRitchie Hayne was contracted to do that job. He was paid $5 for the use of his team of horses. It took them almost two days to reach the lake. They arrived and the work of repair finally began.[21]

Some of the local men were hired to assist the air force in the repairs, Wilmer Hodgson amongst them. Mac Martin was hired as a caretaker to secure the site and safeguard the plane when the workers were finished for the day. Harry and Garfield Hodgson were also hired. They assisted the skilled technicians who were also billeted at the Hayne and Hodgson homes.[22]

Wilmer Hodgson recalls that the aircraft was on the lake for two weeks or more. Wilmer remembers too being paid five dollars a day for the work. The aircraft was valued at $250,000 in 1944.[23]

So the salvage and repair began in earnest. Wilmer’s account gives great insight on what measures were taken to salvage and repair this plane. He and others cut logs from the surrounding woods. Some of these logs were used to build a jack-stay that was used to lift the broken aircraft up from the surface of the lake. The aircraft was suspended while the broken wing was removed and the replacement wing installed.[24]

The work progressed well despite all the difficulties. The day came when it was finally done and work completed. Forty five-gallon cans of fuel were hauled out to the lake to refuel the plane. This gives a broad hint at the reason and the necessity of the forced landing; the plane was simply running on empty!

The fuelling of the plane marked the end of a journey of sorts. It was the last step in a flight that was supposed to be routine, daily, boring, and uneventful, which began 4 March 1944. It was long overdue reaching its final destination. If anything, this vignette was probably typical of what was a maritime patrol in Atlantic Canada during that winter of 1944.[25]

The Big Day – Flying Off the Lake

There was great fanfare on the day scheduled for take-off. Many walked out to Archibald Big Lake to see the plane take-off. A huge crowd of men, women, and children from the local community gathered on the lake. It was a once in a lifetime event. This was 1944 and rural Nova Scotia after all. You just didn’t see a warplane take off from a Country Harbour lake every day.[26]

Wilfred Langley recalls the procedure on how that take-off was achieved. Holes were made in the lake. The men placed large poles in the resulting openings. Ropes were then tied and tethered to the aircraft. Finally the aircraft`s engines were revved as fast as possible.

The plane strained and shook violently against the ropes tethered to the poles, struggling to be released, and striving to become air borne. The ropes were cut. Away went the plane at full throttle, hurtling down the lake, and then, in a short bit, bolting up to the sky.[27]

This may sound far-fetched but it was typical of the extraordinary efforts and ingenuity used toward the salvage of valuable aircraft at the time. It is an amazing insight to the skills used and problem solving of the day. It was all in a day’s work of getting the job done in what was most likely the most expedient way possible![28]

The reason for the overflights – the U-boat threat

You may ask why the aircraft was flying over Country Harbour in the first place? There was a great deal of Air Force activity over Nova Scotia during the Second World War. Aircraft were flying all over. Obie Fenton’s admonishment to his daughters “you knew when the wheels were down, the plane was going to land or crash” was a realistic appraisal at the time for there were some 300 air crashes alone in Nova Scotia during the war.

Much of this aerial activity was for training purposes but much of it was of an operational necessity too. There was a persistent U-boat threat off Canada’s East Coast. We often think of that as a purely naval show. It was not. The fact was the threat was real and had to be dealt with by Home War Establishment (HWE) through the mobilization of all its assets on the East Coast. This included the Navy, the Army, the Air Force, and Eastern Air Command and a system of Coast Watchers organized around civilian volunteers in particular.

Billy Goobie of Hamilton, Ontario, a former resident of Country Harbour was recruited by the Air Force to be a member of the local observer corps. His home was the location of the local telephone exchange, a good fit for an observer and the requirement for speedy reportage. The Home War Establishment (HWE) and the Air Force had reports that German U-boats had entered the estuary and river at Country Harbour and in the lower shore areas. This was a very real possibility. U-boats could be present in these unguarded waters.[29]

Evert Hudson claimed to have seen one in Country Harbour during the war. He described a surfaced U-boat coming up the Harbour, backing around, and then turning out to sea again. Such would have been a very dangerous action on the part of any U-boat Commander. It seems unlikely that any U-boat Commander would place his vessel and crew at extreme risk and very much in harm’s way.[30]

There are no known records of inland incursions in harbours and inlets such as Country Harbour by U-boats during the Second World War. But there were actions in deeper and wide approaches in the Gulf of St. Lawrence during 1942. The German Navy did have a limited capability of a few U-boats specifically designed to enter enemy harbours and approaches to stealthily lay mines or to lay in attack with torpedoes on enemy shipping when required to do so out of an operational or a strategic necessity.[31] So the threat was very real indeed!

The question has always been how close did U-boats approach Canadian shores?[32] There are news reports and sightings of U-boats anywhere between six and 20 miles off Nova Scotia’s coast line. There were also reported incidents, some very intimate encounters, where surfaced U-boats allegedly approached local fishing boats for food and water. But these sightings were often disregarded either as imagined, unsubstantiated or unverifiable.[33]

The fact is Eastern Air Command (EAC) of the RCAF reported 84 attacks on U-Boats between 1941 and 1945 resulting in six confirmed U-Boat kills. This was quite an achievement given the resources at hand and the relative scarcity of targets relative to operations in the European theatre of war.[34] But the Second World War was very close to home and had come to Country Harbour too! The proof of that fact lies in what was found many years later.

Fast Forward to 2000 Recovery of wing by Robert Walsh and friends

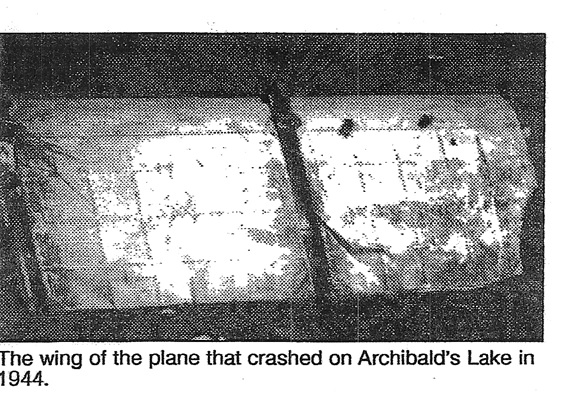

It was at the far end of the lake and within 300 feet of the distant shore that our story takes us to in the year 2000. The plane just didn’t fly away leaving the area cleaned of all debris back in 1944. A damaged portion of the wing was left on the lake. It eventually sank to the bottom in the spring thaw of that year. Why it was left there, is not known. It came to rest in about eight feet of water and left undisturbed until the summer of 2000.

The wing was not a lost or a long forgotten artifact of war. Its location was well known by all in the community. Robert Walsh and others fishing and trolling the lake would often pass over the wing as it was easily noticeable from the surface and thought of as a good place for fish to hide. Occasionally it would be a nuisance due to snags and loss of lures. Troublesome as it was, it was a favoured landmark for some great fishing and conversations.

Robert Walsh, a long-time resident of Cross Roads Country Harbour had known about the wing since early 80’s from the times he used to go fishing with an old friend, Evert Hudson. Robert said “I had thought many a times of recovering the wing but it never seemed to happen. Roy Marryatt, one day said, ‘Let’s do it’”. Robert says “He was the push that got me moving”. They pulled the other guys together and away we went.[35]

Robert and Roy Marryatt (now deceased) organized a team to recover the wing. They had a diver, Marcus Maclaren (Robert’s nephew) and 4 -5 others in the crew. On a grey misty maritime summer’s day Thursday 17 Aug 2000, the team proceed to Archibald Big Lake on the sole mission of salvaging and recovering that wing.[36]

Photograph of Marcus McLaren holding up wing 17 August 2000

Thursday afternoon was spent dislodging the wing from the bottom.[37] Marcus Maclaren, the diver, tied ropes to the wing that were subsequently tethered to two motor boats. Between pulling with the small aluminum boats, and Marcus shoving from the bottom in diving gear, the effort of the team of boats and diver, finally dislodged the wing.

It was carefully floated to shore, where the four wheelers attempted to bring it onto dry land. They failed. The weight of the wing and friction made it irretrievable on the day. This called for a new plan of attack.

The team returned on Friday 18 August 2000. This time the plan was to float the wing onto a boat trailer hauled through the woods by Robert Walsh. The work continued fast apace. The wing was finally lifted from its watery grave onto dry land two hours later, fifty-six years after it was left abandoned on the frozen lake surface!

The team faced the same task as their forbearers did in the recovery task of the downed plane. Would the wing go through the woods? They needn’t have worried. With chainsaws in hand and gingerly progressing down the woods road from Archibald Big Lake, the wing on the boat trailer was hauled 7 km through the woods and down highway 316 to Robert’s home on the West Side of Cross Roads Country Harbour without cutting one tree!

Coincidentally, it turned out to be a two day effort getting the wing out of the woods.

The wing was successfully brought to shore after so many years of laying on the bottom of Archibald Big Lake. Surprisingly many of the fittings and valves were in a good state. The wing was still in pretty good shape all in all. The team noted that a section of the wing had been cut out in the area of the fuel tank. But that was the only visible damage.

The wing was photographed at Robert’s home. He had planned to make a monument and place a plaque by the Remembrance Day that year at the Cenotaph at Cross Roads, Country Harbour. The Municipality of Guysborough would have funded the project to mark the importance of this occurrence during the Second World War.

But their story garnered much attention and media interest. David Powell then a volunteer with the Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum at the Halifax airport convinced Robert and the rest of the team to donate the wing for its collection. The Wing was brought to the Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum for a project in the eventual restoration of a Hudson Bomber within its collection of artifacts.

There are a number of twists and turns in this story. Throughout this tale I have alluded to “the plane”. The question is what plane? The aircraft in question was at first identified as a Lancaster Bomber, a four engine aircraft. It turned out to be a twin engine bomber. It was misidentified again as a Hudson Bomber, a maritime patrol aircraft widely used on anti-submarine patrol at the time. The Hudson Bomber was well known and was operating both out of Debert and Greenwood.

But the newspapers of the day never identified the aircraft type in the clippings … so it was always assumed that it was a Hudson bomber. The Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum (ACAM) identified the wing to be from a Ventura Bomber, which was a different aircraft but a model built to be a re-engineered improvement based on the Hudson bomber airframe.

The Lockheed Ventura was operated by many allied air forces and the air force was in the process of gradually replacing the older Hudson types. It also came as a shock that the wing recovered from Archibald Big Lake had clear US naval markings and insignia.

It is very clear that the wing tip and back edge of the wing in the above photograph are missing. Mickey (Fenton) Harpell’s picture below is what may be the missing artifacts, the landing flap from the wing picture above. This artifact too were widely known and used in the community after 1944.

A long piece of this wing may still be lying in some local field.

Still a number of questions on the aircraft’s origins remain. Was it a US crew that had actually gone down on Archibald Big Lake during the Second World War? Where did it originate from? What was its mission? What actually happened?

So whose plane was it? The news accounts of the day clearly state that that the aircraft was from Dartmouth. We must assume until proven otherwise that it was a Canadian crew and a RCAF aircraft.

It transpired that in the exigencies of the war, aircraft were transferred from the United States to Canada on the lend lease program. These were often flown with US markings until they could be re-painted on a maintenance cycle.[38] This is what we know from news accounts written in 1944. The rest of the questions remain a mystery to be solved!

Fast Forward one more time to 2015

The wing that Robert Walsh and his team recovered in August 2000 and the fuselage of Hudson Bomber from the ACAM are now being restored as a museum piece. This restoration is currently underway at Trenton, Ontario at the National Air Force Museum in association with the Atlantic Canada Aviation Museum (ACAM) in Halifax.

The project is the restoration of the 1942 Mark VI Lockheed Hudson, Serial Number FK466. It will be the only Mark VI Hudson on display in the world. The project will take five years to complete.[39] You may be surprised to learn that the wings of the Ventura and Hudson Bombers were interchangeable. The Ventura wing from Archibald Big Lake is being used in a very historic restoration!

Canada owes a debt of gratitude to the citizens of Country Harbour. First and foremost, for their boundless efforts in the rescue of the aircrew and salvage of the airplane aircrew at the height of the Second World War. Their friendship, hospitality, and succor to the downed air crew must have certainly been most appreciated by those there.

Second, Canada owes a debt of gratitude to those who followed. They remembered. They have never forgotten those events as they caringly brought a historic artifact out of the woods, which is about to have a new life. This year marks the 15th anniversary of the wings recovery from Archibald Big Lake.

Robert Walsh and his team remembered the supreme sacrifices made by our predecessors during the war in this effort. Their hope was that somewhere in the community, a fitting place would be found to mark the importance of this occurrence during the Second World War.

That place has now changed and will be at the National Air Force Museum at Trenton, Ontario. The restored wing on the Hudson Bomber, a significant part of Canada’s aviation history, will be displayed for all to see. A debt of gratitude is owed to them for their generous donation.

The Treasure Trove – The value of family albums!

Many stories are yet to be discovered and told. Sometimes all it takes, is one picture to prick one’s interest. Such discoveries have led to two stories from Guysborough County alone on the vibrant history of Canada at War on the home front during the Second World War. The Girl on the Wing and Mystery on the lake are two examples of these possible discoveries, those hidden treasures in family albums and scrap books.

Does one exist for you? You never know what’s waiting for you in that old family photo album or just sitting waiting in that shed or barn. Just open them up and relive the memories of Mom and Dad, their parents, siblings and your community. It’s all there for you to discover!

[1] Santa Ana Register, California, untitled item; Southern Cross. Datelined TRURO, N. S., June 26, Page 1, Accessed: 5 June 2015

[2] Ibid Santa Ana Register, Datelined. TRURO, N. S., June 26, Page 1

[3] Files from Norma Cooke, 8 June 2015 “A.D.C. Aids in finding lost fliers, 1944” (newspaper and author not identified) scrap book

[4] Files from Norma Cooke, 8 June 2015 “Aids in rescue, March 1944” (newspaper and author not identified) scrap book – this section unless otherwise noted

[5] Files Gina Walsh, Cross Roads Country Harbour, 8 June 2015, “Salvagers go on a wing and a hunch by Brian Hayes 21 August 2000”

[6] Files Norma Cooke, A.D.C. Aids in finding Lost Fliers, (news clipping 1944)

[7] Mickey (Fenton) Harpell/ Gerry Madigan Interview, 23 Jun 2015 @ 1940-2010 hrs

[8] Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, Plane crash of 1944 recalled, Guysborough Journal, Thursday 11 October 1990

[9] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell, 23 Jun 2015; and

Beulah (Fenton) Myers/ Gerry Madigan Interview, 23 Jun 2015 @ 1315-1335 hrs

[10] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, 11 October 1990

[11] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, 11 October 1990

[12] Wilmer Hodgson/Gerry Madigan Interview, 23 June 2015 ,Time: 1335-1410 hrs

[13] Crash Record USN, Card# 1345, PV-3 #33932, 23 February 1943

[14] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, 11 October 1990

[15] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[16] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[17] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, 11 October 1990

[18] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[19] Files Gina Walsh, Brian Hayes, Salvagers go on a wing and a hunch, Chronicle Herald, 21 August 2000

[20] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Brian Hayes, 21 August 2000

[21] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Brian Hayes, 21 August 2000

[22] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Brian Hayes, 21 August 2000

[23] Ibid Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[24] Ibid Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[25] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[26] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[27] Ibid Mickey (Fenton) Harpell and Wilmer Hodgson, 23 June 2015

[28] James Montagnes, How the RCAF Prevents Waste, Aviation – The oldest American Aeronautical Magazine, March 1944, pg. 168-169 & 324. (pg. 169)

[29] Ibid Files Gina Walsh, Sarah Mason Wilson, 11 October 1990

[30] From the interview file: Robert Walsh Interview 8 June 2015, Time 1230-1330 hrs

[31] CBC News, German U-boat found off Nova Scotia, 14 July 2004, Accessed: 9 Jun 2015

[32] Tristin Hopper, Group on mission to prove there is truth in legends that Nazi submarines went far inland from Canadian coast, National Post, 19 April 2013, Accessed: 14 June 2015

[33] Some examples from “Canadian War Museum archives, 149- War European -1939- Submarine Warfare -Atlantic Coast:

- Hamilton Spectator, Submarine Reported Off Nova Scotia, 21 September 1939

- Globe and Mail, Unidentified Sub Sighted Twenty Miles Off N.S. Coast, 29 September 1939

- Hamilton Spectator, Undersea Craft Said Observed Off N.S. Coast, 2 October 1939

- Hamilton Spectator, Fishermen Assert U-Boats Now Becoming Common Sight – Reports of Six Separate Meetings in Atlantic Are Reported, 1 May 1942

[34] Hugh A. Halliday, Canadian Military History in Perspective, Hunting U-boats From The Air: Air Force, Part 15, Legion Magazine, May 1, 2006, Accessed: 22 March 2011

[35] Robert Walsh- Gerry Madigan, Interview 8 June 2015, 1230-1330 hrs

[36] The wing recovery previously documented see:

Files Gina Walsh, Cross Roads Country Harbour, 8 June 2015, “Salvagers go on a wing and a hunch by Brian Hayes 21 August 2000” , and

Matthew MacArthur, WWII plane wing moved from watery grave after half a century, Guysborough Journal, 23 August 2000

This iteration is drafted based on the notes from interview of 8 June 2015 and clarification of those files by Robert Walsh.

[37] Matthew MacArthur, WWII plane wing moved from watery grave after half a century, Guysborough Journal, 23 August 2000

[38] Information provided by Chris Charland, National Air Force Museum Canada and Christian Larsen, Pennfield Parish Military Historical Society

[39] National Air Force Museum of Canada, Lockheed Hudson, Copyright 2015, Accessed: 7 Jun 2015