Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted for the generous help and time of many people who allowed me to use their photographs, peruse their scrapbooks, archives, and even mailed me valuable leads and content! All these have proved invaluable to compiling and writing this article.

I truly thank the following for their most generous help and encouragement:

- Mary and Brian Richard, Larry’s River, for the interview and permission to use pictures and archives as well as for their time and effort for the site visit to No 5 Radar Unit. That site visit was invaluable to understanding the life and times of war time service there;

- Norma Cooke, Isaac’s Harbour, her many letters, comments and use of her archives and who first brought this story to my attention;

- Royal Canadian Legion Cole Harbour Branch 46 Canso for permission to use Mickey Steven’s files, photographs and record in the recounting of this story; and

- The author would also like to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to the late Mickey Stevens who left the community with an excellent record and outstanding legacy of his personal history and for recording the stories and history of his time at Cole Harbour.

“For the good times”

– Through the eyes of Mickey Stevens

No. 5 Radar Unit (RCAF)

Cole Harbour, Guysborough County, NS

1942-1945

By Gerry Madigan

11 December 2015

“Nothing ever happened here in Canada during the war.” It is amazing what may be said and discussed over family BBQ. We were sitting around discussing some local history when that one was made. There may have been a kernel of truth to it. It was hard to dispute because much of what Mom or Dad did during the war much less in Guysborough County was never discussed and was considered unimportant to them. How many times have you sat around the family table reminiscing about times passed when this question was floated “I wished I asked Mom or Dad about that?”

The summer of 2015 was a busy one for me. My regular fishing season was interrupted by a number and demands of research projects concerning the history of Guysborough during the Second War. These projects are normally reserved as an indoor activity over the fall and winter months. But mother nature and chance intervened with my plans. The fishing was absolutely lousy last year…at least for me. So it proved that those projects proved most productive and very enjoyable to me. They also proved and dispelled the comment “Nothing ever happened here in Canada during the war.” A lot did happen!

So it came to be that chance intervened with my fishing plans that resulted in one of the most productive writing seasons that I ever had. I became heavily involved in four projects. Three were or about to be published in the Guysborough; “Girl on the Wing”, “Mystery on the Lake”, and “What’s in a name”. Some the readers may recall these. The fourth project was a personal study and a paper on the Ventura bomber for Pennfield Ridge Historical Society New Brunswick. All these projects demanded a lot of my time and occupied me well until late September.

I thought I was completely done with the history of Guysborough County during the Second World War. I was wrong, it had only just begun. Norma Cooke of Isaac’s Harbour has been very supportive of my research efforts. She provided me with a lot of background information that I used throughout the summer. Norma spoke with me back and forth over the summer. Norma knew that there was more out there and wasn’t finished with me yet. She asked “would you be interested in having my files on No 5 Radar Unit at Cole Harbour?”

To be honest by the time she raised the question I was ready for a much needed break for I just started my lost round of fishing trips for the season. I wanted to increase my dismal fishing season and to improve my catch and release numbers. The long and the short of it was Norma sent along her files and the name of a contact, Mary Richard at Cole Harbour. My initial reluctance to pursue any research on the issue was soon replaced with enthusiasm. I read the background information Norma provided and found a wealth of information on No 5 Radar Unit (RCAF) on line. The author of many of the stories was Sgt Mickey Stevens of No 5 Radar Unit (RCAF) Cole Harbour.

Mickey’s stories are in fact valuable historical gems and a time capsule of the life and times of Guysborough County during the day. Mickey’s stories are the Unit’s history and context of their lives that is so often sadly lacking when conducting such research. Sometimes the facts too hard to find and buried so deep in the archives, that a project quickly becomes very discouraging and quickly abandoned. But Mickey’s accounts laid it all out there and were full of history too! Uncharacteristically for a historical record, they are a fun and a humours read too! More importantly Mickey’s accounts addressed the issue of “Nothing ever happened here in Canada during the war. They do address that assumption head on!

A lot did happen here at home. That story of the war is often overshadowed by what happened overseas. It wasn’t all fun and games in Canada. There was much hardship endured and shared by all. There were both good times and bad. Mickey shared them all. His account is one of a shared experience amongst communities. The experience brought altogether too that bonded both the military and civilian communities in a very close relationship that was very uncharacteristic for wartime Canada. Those nearby communities became very closely attached to No 5 Radar Unit and vice versa.

This humble account retells some of Mickey’s experiences, remembered for the good times. It is also a reminder that something did happen here at home!

Getting Started – Construction and Manning

No 5 Radar Unit of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) at Cole Harbour Guysborough County Nova Scotia was one of operational radar units on Canada’s East Coast during the Second World War. It came to be in August 1942 and existed for three years to September 1945. This would be Mickey Steven’s home over the course of the war. He had two postings there, the first as a simple LAC, the second after some additional training, as a sergeant.

We start this story much like Mickey with a simple walk through time. We arrive at Cole Harbour and proceed up a mountain road to arrive at up on the barrens above Cole Harbour. If we did that today, we’d find nothing much there. When Mickey first joined the RCAF before 1942, there was nothing much there too. Mickey had to be recruited and trained first. In the meantime while he was doing that the radar chain was being built.

The actual planning for a radar chain in Canada began in 1940. It was a slow process. There were two phases to the implementation of Canada’s radar defence chain. The first phase involved the selection and construction of the sites. The second phase was making them operational that involved the training and manning of them.

Much had to be done between planning, conception and construction. Siting of these units had to be and completed on both East and West Coast of Canada first. Equipment orders had to be placed. Staff had to be trained, and on site construction begun. The first stations only became operational in 1942 and the last station completed in 1944. [1]

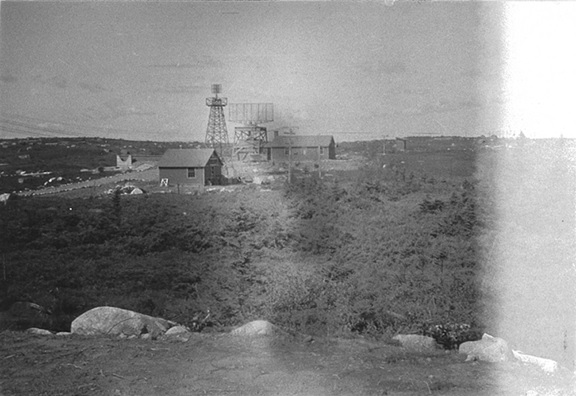

No 5 Radar Unit (RCAF) was built at Cole Harbour, Guysborough County. The site on the barrens above Cole Harbour was selected because it was 300 feet above sea level and gave a visual horizon of about 20 miles. The official description of No 5 RCAF Radar Squadron’s location was on Tor Bay, approximately 125 east of Halifax.[2]

No 5 Radar Unit was situated on the barrens one and a half miles as the crow flies on Second Cow Lake, north of Cole Harbour. But “as the crow flies” can be very deceiving concept. The walk to Cole Harbour from the station was 2-1/2 miles alone. It was a walk that many airmen took to escape the station and if only enjoy a few pleasurable moments of peace at Cole Harbour.

No 5 Radar Unit location was originally attributed to Queensport. But that changed once construction of the station and the installation of the radar was completed. Once it was manned, up and running, it was officially re-designated as No. 5 Radar Unit, RCAF Cole Harbour Nova Scotia.

Regardless of what community was identified, the men serving at Cole Harbour came to have deep feelings, affections, and many fond memories of all the communities including Queensport, Cole Harbour, Port Felix, Guysborough, and the surrounding area. These communities and the people there became a home away from home and, more importantly, they became friends.

It is a very compelling story and the experience of the servicemen serving there. Theirs was quite different experience compared to the service at large units and at urban centres. Rather than a separation between the military and civilian, there was an integration of people not seen elsewhere. It may have been due to the isolation of this unit, the communities, and their proximity. They had no one else to rely upon but one another.

The actions of the communities was truly singular and lost in the mists of time. This is the story of the common and shared effort made there. It is a story marked by both great joy and sorrow. In the end, it would be the story of what was accomplished in Guysborough County during the war.

The Arrival September 1942

The battle of the Gulf of St Lawrence was waged in the approaches and coastal areas of Canada in 1942. The enemy boldly entered these waters and torpedoed and sunk over 22 ships before I was over. They became a cause for extreme concern and public safety as they were a threated Canadian commerce and security.

Enemy submarines were of concern and considered a priority threat at the beginning of the Second World War in 1939. Canada was most fortunate that the German Navy was most unprepared for war at that point. It would be two years later before the U-boat would pose serious harm in the western Atlantic. It would seem that we had time to deal with that threat.

In the meantime though Canada was not idle. New bases were prepared and opened in the Maritimes and Newfoundland to deal with that threat.[3] The radar detachments would be integral to those preparations, which heretofore were concentrated in Atlantic waters. But their entry into the Gulf was a game changer whose presence suggested an urgency to get things done. One of those urgent measures was the institution of a radar chain.

There were 30 radar sites in the chain around Canada’s east Coast. They had different functions involving:

- High flying early warning radar

- Chain Home Low flying early warning radar

- Ground Control Intercept Radar

- Microwave Early Antisubmarine, surface Radar, and

- United States SCR270/271 Radar.

No 5 RCAF Radar Squadron was one of the Chain Home low flying early warning radar detachments.[4]

The second phase of the radar chain, which ran in parallel and in tandem to its construction and installation, was the training and preparation of the necessary personnel for its operations. There was a wide variety of skills and trades required at No 5 Radar Unit that involved everything from cooks to clerks, from mechanics to medics. All played a crucial role but what was needed most was trained radar personnel and officers if the venture was to be successful at all.

Radar was still relatively new. The training was conducted at Clinton, Ontario. Clinton was the central clearing house from which Canadian recruits from all over this great country were soon be dispatched to their various posts overseas and duties on Canadian Shores.

Canada drew upon its universities from which it selected and trained the officers and radar technicians for this much needed service. Training was also conducted Research Enterprises Limited at Scarborough and a Royal Air Force (RAF) School at Clinton, Ontario. The recruits were posted to their duty stations once they graduated from this system.[5]

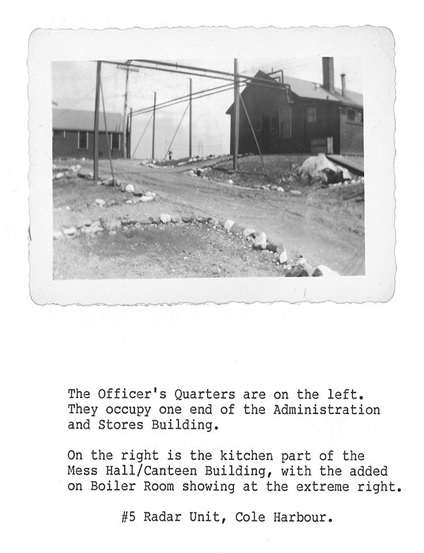

The day came when all was prepared and the first group of personnel began to arrive at Cole Harbour in September 1942. Amongst the first group to arrive was the newly trained LAC Mickey Stevens, radar man. The summer of 1942 had been spent in the erection of H-huts and the radar unit. All the building were pre-fabricated so there it took no time in building and completing the Camp. But “completion” was a misnomer.

The H-huts still had to be fitted out with heating and other amenities. The first priority though was making the radar operational. All the creature comforts would come later. But the men had an expectation that the facility was ready for occupation, it wasn’t. The first few months were spent under some very trying conditions. They may have been sheltered from the elements but they were living there essentially under canvass. Heat was in short supply.

Their spirits may have been dampened somewhat as they crested over the hill and the camp came into view. Their new home was a wild unsettled sight.

Many endured the long trip from the train station jostling in the back of an open box of the 4×4 quad truck over some very rough and unpaved roads. That journey was arduous enough that may be they would be glad to arrive at their new home.

But what a home. They were really out in the middle of nowhere and were largely on their own. The one good thing though was that they had electricity. Electricity was a necessity, the lifeblood of the station. It was the sole source of power for the station and for the operation of the radar unit. But it wasn’t NS Power. That electricity was self-generated in a small garage size Diesel hut.

The station had three Caterpillar D1300 diesel generators that powered the unit. They were independent for all other supplies and reliant of r-supply of fuel and stores to keep them going. They also had a steam heating plant to keep them warm. But heat was still a luxury in September 1942. It would be a long time before all the facilities were fitted for steam heat…and winter was just on the horizon.[6]

They would soon find out how isolated they truly were. That isolation was punctuated by time and space that made life their both interesting and challenging. Service at No 5 Radar Unit was not for the faint of heart.

Food, Food, Glorious Food – Hardtack and Stewed Tomatoes

Food is a force multiplier. It is the one thing that greatly affects morale of the troops for good or bad. The one big question that everyone had on their minds upon their arrival at No 5 Radar Unit was what was the food like? Was the chef any good?

There was good reason to wonder. There were many variables to consider. Their supplies had to be brought in at a great distance from an Army Supply Deport located at Mulgrave. There was no easy trip to the grocery store. Their re-supply runs were also limited by the size of and what the truck could carry. Finally there was always the issue of weather and road conditions.

The roads were rough and unpaved leading into No 5 Radar Unit. They would be easy to navigate in the summer and fall but any lick of snow or wet weather, often meant an epic journey for the re-supply run. So it would be natural to wonder what the quality and quantity of food would be like.

The first meal in 1942 at No 5 Radar Unit remembered by Jim Vaughn was simple fare. It was mid-August. The Unit was still under construction. There was only a rudimentary staff with one cook. The cook had very primitive facilities, there were no bunkhouses ablutions or other facilities ready.

The men were bedded down in a partially ready administration build. It was to be “a regular camping trip” for them. Somehow though the cook managed to come up with a maritime favourite, baked beans and biscuits. He fed a hungry group of men, which was cooked on a stove outside the administration building.

The men sat around in the open on benches and chairs. At that point, everything affecting station morale rested squarely on his shoulders. It was a testament to his skill that there were no complaints about the cooking!

Canada was affected by wartime rationing too. This would limit the variety and availability of food stocks. It even affected No 5 Radar Unit. But No 5 Radar Unit fared surprisingly well. The menu was an institutional menu that ensures all had the proper balance and amount of calories for a healthy diet. But institutionalized food soon became monotonous and boring.

No 5 Radar Unit relied on the Army for its provisioning and support. The Air Force was not large enough to have supply depots freely distributed all over the country for its own needs. It was a common practice that the Army was the central depot for many services for all forces units in their geographical vicinity.

This was both good and bad. It reduced the foot print needed to support Canada’s armed services. It enabled a common system for supply and administrative support but… when and if there were shortfalls, those shortfall would be shared by all…or so it was said.

It came to pass that No 5 Radar Unit received a quantity of hardtack and stewed tomatoes on a supply run one day. These were hard rations. Hardtack was meant to be used in an emergency or last resort. The first shipment was probably accepted and nothing untoward thought about it, and regarded as just one of those things given the state of rationing. But the second shipment of hard rations was more spurious and was as an insult to the palate. Hardtack was good for one of two things, breaking teeth or target practice.

It happened that the Stake truck was out the supply run with this second shipment. It had a number of passengers aboard who most likely there when the first shipment had been received. They found the Unit was once again being resupplied with hardtack. They were shocked and greatly displeased. The passengers took matter in their own hands and proceeded to open and launch those hard biscuits at any target of opportunity along the road all the way back to the Unit.

It must have been a considerable quantity of hardtack that lay strewn across the country side. It may seem like a waste of resources but rather than incurring the CO’s ire, they had his expressed gratitude! It ridded him of the effort of tossing the stuff off station for it was not fit for man nor beast. It was said that his blood pressure rose every time he saw and passed those slowly disintegrating biscuits along the road whenever he was out and about. It disturbed him so much that he raised a complaint and blasted the Army Depot. No 5 Radar Unit never received hardtack again!

The inmates of No 5 Radar unit wrongly assumed that as they were by the Atlantic coast, fish was to be a big part of their diet. That assumption was soon put to rest. It would be 10 months before they saw an actual fish dinner. No one officially knows why. Fish was probably not available in quantity. It was quite likely in very high demand and needed to feed the hungry mass of city dwellers now that meat was strictly rationed. Eating fish was ways and means of reducing that consumption.

Meatless Tuesdays was one thing that was done on a grand scale. The alternate proteins were either legumes or fish. So fish may not have been available locally or in quantity in the Army ration system. If the boys wanted fish, then they would have to buy their own stock with their own mess funds and that was often done.

It wasn’t just fish or meat that were in scarcity and rationed. This scarcity extended down to fresh fruit too. The Annapolis Valley is famous and known for its abundance of apples. But apple growing and distribution were closely monitored during the war. The idea was to maximize and preserve the crop. That usually resulted in the canning the crop for future use. Huge quantities of apples sauce were readily available but try and find a fresh apple…well that was another thing.

Mickey Stevens knew his Canadian geography well and decide to take one of his valuable leave in the Annapolis Valley to help with the apple harvest in 1943. His sole mission was to procure and to bring a barrel of apples back to the Unit so the boys could enjoy a fresh one.

Mickey found an apple orchard five miles outside of Kentville. He went in to meet the farmer and explain his mission and plight. Mickey wasn’t tossed out on his ear but was invited in and had dinner with the family. The farmer explained that he couldn’t sell him any apples because his crop was under the total control of the marketing board. This explained why there were huge quantities of apple sauce but no fresh apples at the station.

The farmer was sympathetic to Mickey’s plight though. He couldn’t sell Mickey any apples, but he could donate them to the station! They had agreed to an arrangement. Three barrels of apples weighing 40 lbs apiece were sent C.O.D. to cover delivery charges to No 5 Radar Unit.

Mickey accompanied the barrels of picked up the apples back to the Unit. He sold the first barrel at a nominal charge to cover the freight and his costs. The remaining two barrels were donated and enjoyed by everyone in the Mess. It was one of Mickey’s more successful adventures.

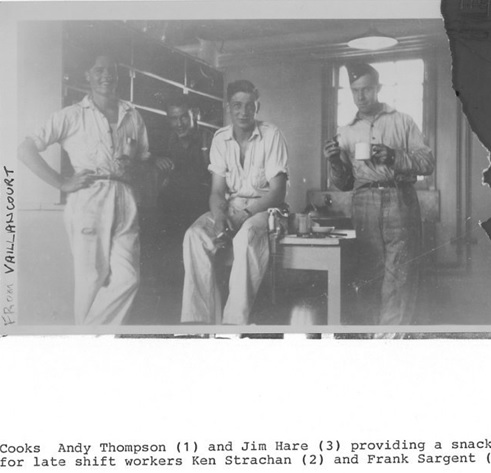

But as the Unit settled in things became a little more relaxed too. The Unit kitchen was a busy one. The Cooks were a sympathetic lot. The kitchen wasn’t necessarily out of bounds. They realized that they couldn’t be on call 24/7. The Unit was their home, and the kitchen a part of that home too.

The Head Cook, Cpl Walter Harvey allowed the rank and file the use of the facilities to make their own snacks and other fare…as long as they left it in a clean state. The inmates never failed in this promise. The cooks could get at their work every duty day without a major clean-up. Their faith and trust was not abused. The men kept the kitchen clean and spotless.

It was very much a home. All were welcome to satisfy an eclectic mix of eating. Some airmen would show up with a couple of friends from a fishing trip. Here they cooked a mess of trout for al to enjoy. Others simply nipped down to the village to bring back a few lobster. Sometimes it was the simple desire for comfort food. A simple a can of pork and beans on toast was often a treat! No matter the mess, it was always cleaned in time before Cpl Harvey’s duty day began.

But not everyone had simple tastes in their quest for gastronomical delights. No some people had very unique and sometimes rustic tastes that needed satisfying. Morris Rachlis was from Winnipeg. He had very unique tastes. Morris had a hankering for pickled herring. How anyone from Winnipeg acquired such a taste was truly mind boggling. Trouble was there was no pickled herring to be had locally.

Rachlis decided to make his own. He acquired the herring then proceeded to pickle them… in the sinks….of the washrooms… of the station. Rachlis used 8 sinks that he marked out of bounds and barred from further use. The question is and we’ll never know the answer, “Was he ever successful at making the pickled herring?”

Rachlis’s story explains the lengths that men go to satisfy their hunger.

“Food glorious food” was a refrain from the musical “Oliver”. It is the one thing that is always on the minds of hungry men. But it was more to it than hunger, there was that need for comfort too.

The problem was given the location you couldn’t always for easily get away for meal in Guysborough at the Grant Hotel or other locally eateries…sometimes you just had to make do with what’s in the kitchen at home. That kitchen of No 5 Radar Unit was part of their home away from home!

The Chicken Coop – where rotten eggs came home to roost![7]

Military dictum that states “Be 10 minutes early for a meeting”. A military organization is ruled by time. The importance of this rule cannot be understated or under-estimated! Sometimes, time is the difference between life and death, at other times, it can be the measure between reward and punishment. Time is the one thing that drives servicemen to exasperation, for time isn’t their own!

Canada’s servicemen during the Second World War were first and foremost drawn from civilian life. The adjustment to military life was a yoke on many shoulders where once the uniform was worn, the bearer realized that they had lost a great deal of their civilian privileges and, most importantly, the right to do their own thing. For some this adjustment is downright painful. For others, it became a game and a challenge to see what one could get away with by bending the rules.

Under military discipline there is always an expectation that once an order was received, it was to be obeyed immediately. It was especially so on a posting order. Usually there was sufficient time given for a serviceman to get to his proper station. It was always up to the serviceman though to get there without fail even if problems were encountered along the way. That’s the reason behind the dictum “Always be 10 minutes early for a meeting”, you had to plan to be there before your time if you were to avoid any trouble.

No 5 Radar Detachment at Cole’s Harbour was an out of the way place. It was isolated and hard to get to. It may have been the reasoning for the newly graduated radar man, Harry Brewes, to conclude that he had some leeway in his delaying his arrival time. Brewes recently graduated from the Radar School in Clinton Ontario. He was awaiting his posting near Scarborough while at Unionville training facilities. Time weighed heavily on his hands.

Harry’s situation was fortuitous for he had time for other endeavours more to his liking. He was close enough to court his girlfriend, Helen. But his sunny days were to soon end. He had received his order to report to Cole harbour. Harry thought this posting to the east coast would be the jumping off point for a tour overseas. He also thought that as he would probably not see Helen for a good; long time, it was a good time to asked her to marry him. Helen accepted and they were engaged.

So he and Helen celebrated. Harry delayed his arrival at Cole Harbour by five days. He was technically AWOL (away without authority). Needless to say that Harry was in big trouble by the time he arrived at Cole Harbour. His new CO, Flt/L Clarence Jones, may have had some sympathy for Harry’s situation and Harry may have had some reasonable travel excuse for the delay, but engagement was not one of them.

It was a common enough occurrence in the day. Many young people made such a momentous decisions. But those personal decisions were not to get in the way of military orders. Flt/L Jones made a decision too. Harry would get some digger time in the cells for his absence. Harry was charged, found guilty, docked five day’s pay and given five days in the cells, to be exact. But to Harry it was probably well worth, as he was with the lovely Helen for a few more precious days!

Harry arrived at about the time the Camp was first occupied in September 1942. The new facility housed 36 men. It had messes, administration buildings, and radar. More importantly it had a fully operational guardhouse, one of the first priorities to have been completed. This was where detachment of military police operated. Their post had a cell and room and from which they ventured forth to patrol the perimeter and guard the facility from harm. Harry was very their first guest.

The guardhouse had its own heating system for it was used by the contractors as the project headquarters during the construction of the station. They wanted to be comfortable while they were there. That was very fortunate for Harry too! The coal and wood stove in the guardhouse really put out the heat on those now cooling nights!

The Airmen’s Barracks was still several weeks away from completion, and was cold and damp. The barracks lacked proper heating and hot water systems. Harry arrived at a time when the days were pleasant but the nights were bone cold. So those airmen in barracks were cold and miserable while Harry lived the Life of Riley and in comfort!

Harry reported his stay in cells a most pleasant experience at that point. The Service Police and Security Guards, unused to having guests treated him very well. They even brought him magazines and chocolate bars! To top it off, the cells were even more comfortable as they were also the storage for area for extra mattresses.

Harry would have completed his penance in the lap of luxury had it not been for the CO’s visit. Normal military routine requires the inspection of the prisoner to ensure of general his well-being. This task is normally performed by the duty officer but on this day Flt/L Jones did those honours.

Harry was in cells for two days when the CO finally stopped by. Flt/L Jones was more than a little gobsmacked at Harry’s situation. It didn’t take Flt/L Jones long to see just how Harry was suffering. He ordered him immediately out of cells and back into the cold barracks with the rest of the crew. Justice was finally served after all, at least in the mind of Flt/L Jones.

The cells were little used during the war. There was only on other occasion were a malefactor served any time there (but that is another story). So what happened to Harry? He married Helen of course, and Mr. and Mrs. Brewes lived a long and happy life after the war near Powassan, Ontario of course! So Harry passed the test of time.

Planes, Trains, and Automobiles

No 5 Radar Unit finally settled down into a regular routine that fall of 1942. Mickey Stevens and his mates were out on the barrens, at an elevation of 300 feet above sea level with a visual horizon of 20 miles. They had work to do though. The Radar was fully operational and the IFF masts built, tuned and calibrated. They were ready for war.

A series of overflights and approaches was likely done that fall to test the station. Once the station was calibrated and the communications protocols and systems in place with EAC, No 5 Radar Unit was ready and operational. It commenced a dutiful watch for both enemy and friendly aircraft as well as for enemy submarines.

But it was planes, trains and automobiles that set the tone and was the cycle of their lives. The radar unit had to be calibrated constantly. There were always aircraft in the air that tested the facilities operational readiness. Operational readiness was the prime requirement. In order to do that they also relied heavily on trains and automobiles. This first would be the unit’s test of space. It was the distance from and to their supply depot that would be problematic for them.

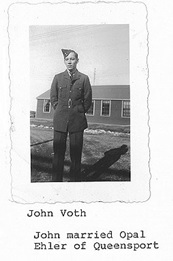

Mickey Stevens photograph – Archives of Mary Richard with permission

The unit had to be maintained and resupplied with fuel and food in order for the station to remain operational and do the job. No 5 Radar Unit was vulnerable. The supply run was easy enough in the summer and fall. The roads to the station were most unpaved, and although the travel slow, they were able to be resupplied regularly.

The unit had a number of vehicles to do the job, the most important of which was the 4×4 50CWT Chevrolet quad. It was used to transport both supplies and people from the railhead at Monastery. A trip to Monastery wasn’t always required. Supplies were often transported to an Army depot at Mulgrave where they were picked up.

The regular supply run ensured that the food, mail, other supplies and necessaries all made their way to the station over these roads. But the most critical supply required was diesel. Diesel was the life blood to run the three Caterpillar D1300 generators that supplied the power that ran the radar and for all of the station’s electrical requirements. Fuel was the station’s vulnerability and its Achilles’ tendon!

The resupply run that worked well enough that fall, soon proved difficult in winter! The 4×4 50CWT Chevrolet quad was mounted with a V-plow and wing. It served a dual purpose. In winter, the supply truck was the snow plow. It performed well if there was decent footing.

The road from Mulgrave to Guysborough though proved most challenging. What was often clear on the way out, often times had blown in on the way back from a supply run. The station’s ration truck was prone to being stuck or storm staid in the snow.

There was a particularly bad stretch near Port Felix where there was an uphill grade and where the road would blow in. A call to the station for help was often made. It yielded a crew of volunteers to shovel and clear the road for everyone wanted their food, drink and mail. But oftentimes the situation simply overwhelmed the men and was much too much for the station’s 4×4 50CWT Chevrolet quad. The station’s volunteers were helped out by the people of Port Felix who pitched in in order to clear the road and keep the station re-supplied and operational. Their efforts did not go unnoticed wand was greatly appreciated by the men at No 5 Radar Unit.

The men there knew that they were neither abandoned nor no longer alone! They now had friends in the community who would see them through the tough times and help them out. And there still were some pretty tough times to come. But it was the friendliness of the people that the airmen most admired. They were made to feel welcome.

Out on the lonely barrens north of Cole harbour, a friendly face or chat was a very welcome relief from their very disciplined military lives. It would be the start of a deep friendship that was well remembered over the years and long after the war. But they all shared a common purpose and pride. It was their joint effort by doing their bit and that ensured No 5 Radar unit remained fully operational.

Pride of Unit

The Unit’s first Commanding Officer was F/Lt Clare Jones. He would go to extraordinary means to keep his station “operational”. There was an occasion when the generators had failed. It happened on the duty watch of the night mechanic, again one Harry Brewes. It was a matter of pride to keep his station operational but sometimes events contrived against pride too! This instance was one of those occasions.

Harry Brewes of guardhouse famed too it upon himself to inform the filter room that the station radar was down. It was after hours in the wee-hours of the morning and he didn’t want to wake or disturb F/Lt Jones. Jones was livid that someone had the temerity to inform EAC that “his” station was now non-operational when he was finally informed the next morning. Brewes was given a dressing down and informed that “He” the CO would decide when and if his unit was non-operational.

F/Lt Jones was adamant that the station would be “operational” until he said otherwise! And he would take both extreme and heroic measures to make it so! It came to pass that there was a spell of bad weather. It amounted to freezing rain that threatened to lock and cease the rotating radar antenna. The freezing rain covered the gantry that prevented the Radar from properly rotating. Jones recruited Harry Brewes to help him. They climbed the windswept gantry and fought the freezing rain. F/Lt Jones use a blowtorch to melt the ice while Harry mopped the water away with rags to prevent re-freezing.

There were no medals for the effort but F/Lt Jones’ No 5 Radar Unit operated with distinction. It was his leadership and record was inspirational. His men admired his determination and leadership. The reputation of a man of that calibre quite likely spread to the community. Such a man simply had to be followed and helped by them when the occasion presented and wherever possible. All knew what was on the line. The resupply of the station became a vital and important task where the community actually helped!

“Getting to Know You!”

The Second World War a hard slog for many of Canada’s young service men and women, where many young Canadians desired to see action overseas. But the reality for a good many was the service for their country was done anywhere but where the action was! That service was often here and where it was needed at home, in Canada. For all young Canadians who joined up, they shared one common conviction, the desire to do their bit.

There was a great coming together and gathering of young people. But what happens though, when you throw thousands of young people together, all in one spot, sharing much the same privations, and sharing the same experiences? People eventually get together, sort themselves out, set down to work, and then, look forward to the down time for a good blast and party!

“All work and no play…makes Johnny a dull boy!” so it is said. But the gathering of people also formed firm bonds, friendships, and sometimes love was in the mix as well. But despite the mutually shared experience, there would always some desire to get away on your own. Getting away from it all, was a much anticipated pleasure if you could get the time off or leave.

It must have been demoralizing and dreary in those early days seen in the yawning gulfs of mud, exposed works and cold unfinished barracks. This was what awaited them at days end and was their permanent home for a time. It heightened the need to get away for some normalcy.

Getting away from the station or unit, however briefly to a nearby town, was the welcome respite to dreary days. Unfortunately those posted to No 5 Radar Unit couldn’t simply hop the bus to town. There was no public or other transport available for that matter. The nearest big town or city was a good long ways away. So they hoofed it on foot to the nearest place closet to them, Cole Harbour.[8]

Halifax, Truro, and other large communities, became the major military centres. They had huge concentrations of military personnel. It was as if a mass invasion had befallen them. Those larger centres and their facilities were often overwhelmed because of the huge numbers of servicemen and women. Some towns and cities weren’t very welcoming communities as a result. Servicemen in particular were often quite restricted to what they could do and where they could go.[9] This problem was not unique to Nova Scotia, it happened nationwide.

Michael Dwyer, former Nova Scotia minister of mines, remarked at one

Remembrance Day banquet in the Canadian Legion, November 1941. A young private soldier was his guest and but was barred by two soldiers with crossed bayonets from entering a leading Hotel in Truro. The soldier’s transgression, he was unaccompanied upon entering the establishment in advance of his meeting Dwyer for dinner. Dwyer noted that three such hotels were off-limits to private soldiers unless they were “accompanied” by a civilian at the time.

Mr. Dwyer remarked “While the private soldier is willing to lay down his life overseas, apparently he is not good enough to eat in these places and must go to second and third-class places,”[10]

Such was the prevailing attitude and many doors were closed to the bulk of the military community. The situation resulted in some unfortunate incidents and actions, which caused such a furor that Hon. C. G. Power, the Minister of National Defence, promised to investigate the matter further in response to a parliamentary question put to him by G.T. Purdy (Liberal, Colchester-Hants). [11]

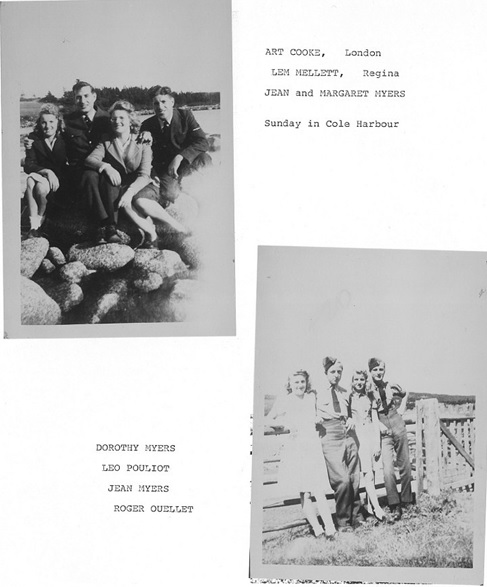

So it was very uncharacteristic for the time, that the experience at No 5 Radar Unit was a very different one. The hearts and doors in the communities near and around No 5 Radar Unit were very much open and welcoming to the servicemen there. It may have started innocently enough. There was more than likely constant contact with the boys from No 5 Radar Unit who walked two hours to Cole harbour just to get away from the station. The treat was the journey to get away, simply for a pop at the local General Store and meet and talk with someone other than a body in uniform.

Then there was also the contact with the station’s stake truck that picked up supplies throughout out the area. It brought news and people back and forth throughout the area. So as the stake truck sallied forth throughout the county picking up supplies, it also built relationships along the way.

The local Legions took a personal interest in the servicemen’s welfare too. They arranged all sorts of entertainment for the men. It arranged and distributed movies and other entertainments to the unit that were certainly most appreciated and highly anticipated. The Legion’s offerings were a welcome happy diversion from station routine that were highly anticipated by all personnel.

Such generosity and hospitality could not be ignored. So the Unit often reciprocated with invitations to the community. Its messes were opened to the community at large for dances and other celebrations to which all were invited and who were made most welcome. The degree of hospitality between the military and civilian communities was very rare for its time. But the true ties are found in the memories and the relationships built beyond the gates and hospitality from those who actually lived and served there.

The village of Cole Harbour was a place where Seldon Meyer’s Family Store was once located long ago. Seldon’s store was a much visited place. Here is where the airmen would see fresh faces, talk and buy some small comforts that often reminded them of home. It was an easy walk, even though in winter that walk would take 3 hours round trip on foot! But the cold deferred very few from taking the walk out. It was a way to pass the time of day with folks, to soak in the village life, and it was away from No 5 Radar Unit!

William Munroe had residence there. It became an important spot for our airmen in early 1943. The Munroe residence supplied the unit with fresh well water. The water quality at the station was simply too poor. The men complained about the water drawn from Cow Lake that bounded the Camp. That water was only good for washing, showers, and laundry. It was totally unpalatable for drinking.

Walter Harvey the Station’s cook became fed up with the constant complaints about the taste of lake water in his cooking. He learned that a local fisherman, William Munroe, in the village, was willing to supply a very limited amount of good well water. So in 1943 Hospital Assistant Scottie Moir was placed in charge of its procurement. The usual trip to Munroe’s well filled three cans but of course because of the demand, there was always a need for constant re-supply.

Scottie never really had any trouble rounding up willing helpers. This was one of those less onerous and more enjoyable Joe Jobs that had some attendant side benefits of exercise and it was time away from the station. But there was likely another reason too! There was always a chance to meet some of the local single ladies.

Seldon Meyer’s had two very lovely and strikingly beautiful daughters, Dorothy and Jean. So his store had their added attraction. They were a beacon to some very lonesome airmen that was probably a great worry to Seldon! But it was worth the hike just for the chance to see and talk with some one of their own age. There was always the hope too for a chance romance, that is, if you stayed on the good side of Mom and Dad. But Dorothy and Jean were not to be the sole objects of the airmen’s affections and attentions.

Wilford “Diesel” Smith served one year at No 5 Radar Unit from September 1942 to September 1943. He was borne Saskatoon, Saskatchewan and was posted from the west to east coast from Alford bay. His long train journey took across the country to Canada’s Atlantic Coast via the Gaspe, where he ultimately landed up in Cole Harbour, NS.

Diesel’s posting was one year at Cole harbour before he was subsequently posted, “overseas” to Labrador in September 1943. But somewhere over that time and along the way, Diesel met and fell in love with the beautiful Edna Alice McCool of Pawtucket Rhode Island!

How that ever happened we will never be truly know. It was out of the ordinary, a Canadian meeting an American…in Cole Harbour…in Guysborough…in Nova Scotia. It seems odd that anyone from Rhode Island would ever be in Cole harbour …but she was! Edna was a cousin of the daughters of Seldon Meyer family at Cole Harbour.

Alice was probably “visiting” and working in the Meyer family store helping out, when one “Diesel” Smith wandered into her life. A possible chance encounter with one young man with time on his hands, with a need to talk to someone other than the same old faces, led to something that changed both their lives forever. “Diesel” and Alice married soon after the war.

Diesel wasn’t the only one to meet the love of his life at Cole Harbour. Jim Vaugh of Parry Sound Ontario met Helen Snow there too. Helen was the local school teacher. She eventually married Jim and they moved to Coldwater, Ontario after the war. John Voth also met and married Opal Ehler of Queensport. So there were some benefits of a walk to town after all!

Oh What a Lovely War

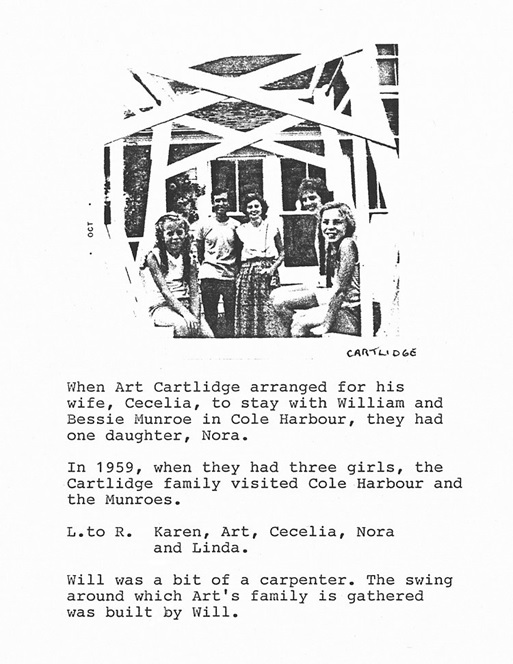

The war was particularly hard on married couples. Couples were forced away from one another and had to endure long separations. But the community of Cole Harbour presented an unusual opportunity for many married servicemen. There were no military restrictions to spousal visits or privately arranged living arrangements.

Many married men rented accommodations for their wives to either visit or live in and around Cole harbour while they were posted there. To the married man it was a bonus. They could walk out to their temporary home but be back in time for a duty shift. So Cole Harbour was a bonus for those married couples who were able to live locally for the duration of the tour.

Jack Minnis of Windsor Ontario made such arrangements for his wife Eileen. She lodged with Wil and Bessie Munroe of Cole Harbour while Jack was posted there. It was a very rare and precious thing for a serviceman to have some semblance of a normal life while on what was really an isolated posting.

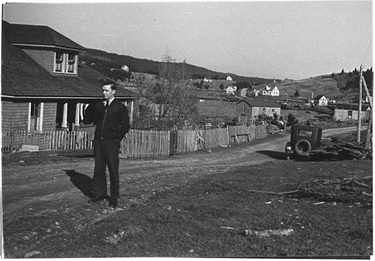

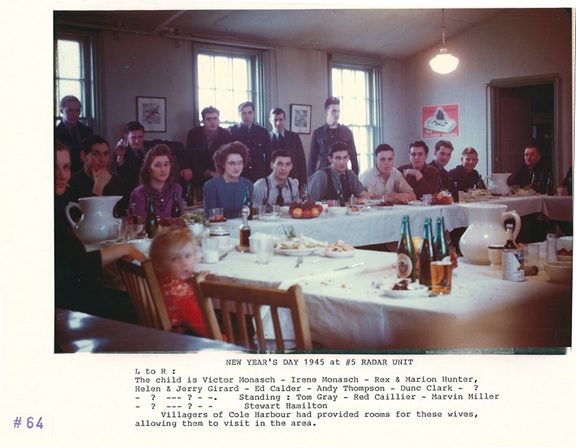

Mickey Stevens photograph – Archives of Mary Richard with permission

And it was an isolated posting. Getting out of Cole harbour to the lights of Halifax or another urban centres was beyond the time limits of a 48 hour pass. It would take you most of a day getting out and getting back in! And at a $1.10 a day pay for a simple servicemen, meant insufficient funds for a good time unless you had save up for a bit.

The only reasonable way out was to have a large credit on your pay account and the time to do so. You had to have time to get out and back. Cole Harbour was a long ways from anywhere. A simple weekend pass simply wouldn’t cut it, especially in winter!

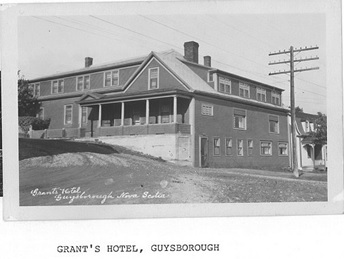

So time, money, and circumstances limited the range of our the wandering serviceman. It often meant that they looked to and took advantage of what was available locally. And the young lads at No 5 Radar Unit they were very fortunate in that regard too. Their refuge would be the Grant Hotel.

The Grant Hotel was operated a by Charlie and Hilda Jenkins. Charlie worked for the county where he maintained and cleared the roads. Hilda ran and managed the Hotel.

Anyone who has spent some time in an H-hut or subjected to military food knows of the need to get away, to sleep and to dine like a normal person. It refreshes the soul and was good for morale. The Grant Hotel became the place for the homesick serviceman for the Grant truly reminded them of home.

Here was a warm place where they could get away from the military even for a short bit. The beds were brass or white cast iron frames with warm comforters. It was a welcome relief from their Spartan life and the drabness of the barracks. The Grant was quite the opposite, there were no fixed bunks or coarse wool blankets to contend with. All was the epitome of luxury and comfort!

The meals….the meals were what every serviceman dreamt of and lived for. They were simply divine, a rare taste of homemade food! And the prices …reasonable; 75 cents for a night and 50 cents for breakfast on fine china. Every meal was excellent! Who could ask for more? More importantly Charlie and Hilda reminded those lonely serviceman of what they missed most, Mom and Pop back home. The Grant Hotel was that welcoming. Many servicemen became repeat guests throughout their stay at No 5 Radar Unit!

The welcome of Cole Harbour, Queensport, Port Felix, Guysborough and all the other hamlets in between is the story about the relationships, bridges and ties that bind between the No 5 Radar Unit and Guysborough County.

Bridges were built, in the visits and meandering, not walls or fences. It was an appreciation of the generosity and spirit shared amongst the people. No 5 Radar Unit had simply become a part of their community! The airmen of No 5 Radar Unit knew what this meant and in no uncertain terms should the people of Guysborough ever forget how much their friendship meant to those young boys who served there! The community became a host and the break from the “routine”.

There’s no such thing as “routine” 1943

No 5 Radar Unit had finally settled down into a normal routine that first fall and winter of 1942 – 1943. The unit monitored and reported tracks along its “arc of fire” in chain of the fledgling radar warning system. It was a day in and day out process. No 5 Radar Unit tracked and plotted aircraft. Most times though, the tracks were limited and only out to 50 or 60 miles. On rare occasions, when the atmospherics were good they were able to plot at great distances, some say well out toward Sable Island!

What they did was important. No 5 Radar Unit and the others in the chain served as a warning post. They monitored of friendly aircraft and shipping off our eastern Atlantic shores. Keeping track of these was vital should any calamity occur. It was at the very least a marker from which the last known plot of a downed aircraft could be used to aid in its rescue.

It was much more than monitoring though. It was also a watch for enemy aircraft and shipping that was of great importance too. The radar chain was a contingency against the potential advancement in developments of the enemy’s technology and strategy too, particularly the monitoring of surfaced U-boats.

But let’s be candid, given the technology of the day, that would be very difficult to do. Radar given the state of its development, at least offered the chance and hope of identifying a potential target where no such hope existed prior its existence. Given the distances and limitations of the technology too, it would be difficult to identify a U-boat that had surface for attack amongst a convoy group. It was exceedingly hard to identify friend from foe.

Then there was the matter of enemy aircraft. Germany did not have any strategic aircraft with sufficient range to strike at eastern seaboard targets. But they did have plans on the books for such aircraft. The Messerschmitt Me 264 Amerika Bomber, and the Condor in particular could have been problematic had they had access to airbases in Greenland or Iceland. The matter was taken seriously by the Canadian government for there were plans however farfetched for the protection of the Welland Canal that was well in the heartland of Canada from air assault.

So whether the threat was real or perceived, No 5 Radar Unit had a very job to do that became a matter of routine and that was recorded and reflected in their daily dairy reports. The daily diary summarized the events of the day and more often than not were no more than one or two lines that marked how routine the work had become.

The routine seldom changed. The diary indicates the pace and rhythm of life much like a heartbeat that was slow and steady, ongoing never changing until 14 March 1943.

The 14th of March started off as a regular day. There were a wide variety of weapons for the unit’s protection and defence at No 5 Radar Unit that required regular maintenance and cleaning. One weapon was the Sten gun. These weapons were used on the unit’s ranges where the airmen maintained their skills and proficiency in their use.

The Sten gun is a close support weapon. Its construction was very simple. It was stamped out of metal, quickly produced, and was easily manufacture. It was a formidable weapon when fired in a fully automatic mode. But it was a no frills submachine gun, a semi-automatic weapon of 9mm calibre ammunition that held in a 32 round magazine. It could be fired in single or multiple round mode.

One 14 March 1943 LAC Butch Buchanan accidentally discharged the Sten gun that he had been handling. There is little detail of how or what happened. The weapon accidently discharged. It may well have been that the weapon had not been properly cleared or that Buchanan had accidently hit an object causing the weapon to fire even if the weapon had been made safe!

The gun discharged and a bullet entered Buchanan’s head just above his left eye and exited the top of his head. Little hope was held for his survival. Sgt GE Daine, Hospital attendant immediately came to action. It is said that Daine performed a miracle on that day. He had very meagre supplies. Daine managed to stem the bleeding, doctored the wound and kept Buchanan alive until Dr Stanton arrived from Canso some 2-1/2 hours later.

Dr Stanton held little chance for Buchanan’s survival. But Buchanan surprised them all. He was still alive when additional help that was brought in from the military hospital at Mulgrave. An additional doctor and nurse arrived and gave Buchanan intravenous fluids. This stabilized him and kept him going until two doctors arrived from RCAF Station Sydney.

Now that Butch Buchanan was stabilized, he was medically evacuated at 7:30 pm that night by air to Montreal where a delicate operation was performed. It took a marshalling of a lot of resources to save him but it was done.

Everybody in Camp wore a long face that day. It was a dreadful accident and showed how fast “routine” could change and become most urgent and dire. The accident showed how clearly how much the personnel of a small detachment became attached to one another. They all worried for his safety and there was a pall on everyone’s mood as they waited for news about him.

News of Buchannan’s progress was closely monitored. Word came down from the Neurological Institute in Montreal on 15 Mar “that LAC Buchanan has improved after his operation.” These words of hope suggested that maybe just maybe, Sgt Daine and the other medical staff had pulled off a miracle! Such simple words raised everyone’s spirits for there was now some hope, however slim, that Buchanan may recover and pull through from his grievous wound.

There was more encouraging news posted in the unit daily dairy on 16 March 1943. The

Neurological Institute at Montreal again gave some encouraging news regarding Buchanan’s condition. Once again, this news perked up everyone’s spirits and gradually things seemed to be going back to normal at No 5 Radar Unit.

There was no news recorded on Buchanan’s condition on the 17 March report. It noted that a movie supplied by Canadian Legion War Services that was enjoyed by all in camp.

The movie helped break the gloom. The Camp dairy commented “Legion has done outstanding work in providing recreation facilities here and their work is greatly appreciated.” Life did indeed seem to be getting back to normal.

Then men wanted to do something in appreciation for all the medical assistance provided in the delivery of LAC Buchanan. On 19 March 1943 a unit committee was organized to collect blood for the Red Cross. The work of this organization brought home to No 5 Radar Unit that it was the blood serum from the Red Cross that undoubtedly saved Buchanan’s life. They all wanted to help out.

Buchanan’s story goes strangely quiet in the unit diary from this point one. The reports of prior days may have given all there hope that Buchanan would eventually recover, be discharged, and sent to some very reputable convalescent hospital for neurological rehabilitation. Regrettably that was not meant to be.

LAC Butch Buchanan finally succumbed to his most grievous wounds most likely on 18 March 1943. The unit may not have been aware of his passing or that the event was too painful to mark in the unit diary. But Butch’s passing was noted in the Globe and Mail on 19 March 1943. The Globe and Mail recorded “Robert Hugh, LAC BUCHANAN, was dangerously injured on active service in Canada”. He was survived by his father J. G. H. Buchanan of Vancouver, BC.

The Stuff of Legend

The late summer of 1944 was one summer when the stuff of legend was born. Flight Lieutenant (F/L) L.B. Monasch was the Commanding Officer at Cole Harbour, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia at the time. Monasch was a well-respected and greatly admired man.

F/L Monasch’s tenure at No. 5 Radar was noted for a hands off approach. His men greatly appreciated that approach. Monasch allowed his men the rare privilege of performing regular duties without his interference nor with the issuance of a lot of unnecessary orders and regulation.

Monasch biggest problem was unit morale and boredom. The duty at Cole Harbour could become routine. The regular tracking of aircraft and the sea-lanes around the eastern shores of Nova Scotia on Canada’s east coast was most important. The situation was also exacerbated by its location. There was not much to do or see on the “Barrens” of Cole Harbour apart from sports, mess, cards, and hobbies. But these too could become routine and boring.

On the one hand the isolation of Cole Harbour this was a perk. It was a settled and idyllic site, way out of harm’s way. So the men were left up to their own devices to entertain themselves but being left up to their own devices also meant that they could get up to no good and into trouble too. So there was little threat perceived that would upset the peace and quiet of station routine.

But boys will be boys and, boys do get bored with the regular routine! The boys needed an outlet and a break from the monotony of life on station. Regrettably there was be few opportunities to do. So if the CO wouldn’t organize one they would do it for him!

Wander down the road to the small communities for the odd pop, treat and local inter-action with regular people just wasn’t cutting it anymore. But that was a long journey on foot too. Some way had to be found soon to a breakaway from the routine and monotony of station life. That opportunity was soon found in the course of their work.

The young men stationed at Cole Harbour were likely amongst the first to pioneer what is known today as “virtual dating”, way before the days of the World Wide Web. The station was linked to the filter room at Eastern Command Headquarter in Halifax by telephone and radio. The filter room was populated with WDs, the women’s division of the RCAF. This was an opportunity to hear the sound of a woman’s voice, so luxurious and rare in their isolated and male domain.

It transpired that when traffic was light or non-existent, the young operators would sometimes engage in some verbal repartee between the WDs and themselves. This was only practiced during the down times or when operations were slow or non-existent. They had to be cautious though because they were under the close watchful eyes and ears of the controller and duty officer. So there was a certain challenge in getting away with it.

These infrequent conservations probably resulted in mutual curiosity, speculation, and sometimes the downright desire of meeting the sultry voice at the end of the line. It must have been a tantalizing prospect. An arranged meeting to get to know one another better or having a date with a young woman of your own age in the dark days of the war was a most tantalizing prospect!

Some dates were indeed made and the young folks met on leave. These chance interludes often led to brief romances, encounters and friendships. Others were more enduring resulting in love and marriage. But whatever happened, it was clear that the boys at Cole Harbour were quite persistent in the pursuit of these young woman. Someone even had the temerity of suggesting an open invitation to the WDs in the filter room to come to Cole Harbour for a visit to see firsthand what the boys had to endure.

This pursuit commenced right at the beginning in 1942. But it didn’t bear fruit until two years later. Results were finally achieved. It may have started innocently enough, most likely with the invitation extended to one young WD. Perhaps there was some reluctance to accept for very good reason on the young lady’s part.

But feminine curiosity must have been piqued at the filter room in Halifax for a visit was indeed agreed to. But it wasn’t just one young woman who showed up on Cole Harbour’s doorstep. No, in fact it was twelve! No reasonable young woman would show up at a station unchaperoned, in the middle of nowhere, only to face the amorous onslaughts of lonely airmen on their own. It was well known that there were at least 30 or more single men at Cole Harbour! There was after all, safety in numbers.

So after 2 years on the line with the boys from No. 5 Radar Unit serving on the eastern shores at Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia, the WDs finally came to town. They were probably just as curious about their male counterparts, of the lives they lived, and of the mystery of those isolated shores as well. So there was much curiosity to be satisfied!

The trip was arranged but without the official sanction of the commanding officer, F/L Monasch. Monasch’s solitude, quiet, smooth station routine were about to be interrupted. We have no idea how Monasch was approached with the news of the impending arrival of the bevy of females from the Women’s Division who were about to descend upon him and his unit. But it could easily be imagined as it may have unfolded in this way:

“Sir we have a problem.”

‘What is it Sergeant Stevens?’

“LAC Barkhouse is on the phone on the duty run to Mulgrave. There are 12 WDs waiting for a ride from the Monastery station.”

‘What? Where?’

“From Monastery to the unit Sir. They say they’ve been invited.”

‘By whose and under what authority Stevens? …what in blazes is going on? Why wasn’t I told?’

“Don’t know sir. They just arrived at Monastery unannounced. It’s late in the day sir… we just can’t leave them there.”

‘Can’t we? Stevens, this is an RCAF station – not a bordello! This is trouble Stevens…nothing but trouble!’

“But if we leave them stranded there, there’ll be more trouble, sir.”

‘Alright Stevens …they can come if they fully understand that:

- there are no facilities for the WD’s at Cole Harbour?

- they will have to ride in the back of an open transport truck?

- it is sixty-five miles to the radar unit, only twenty-five of which is paved?

and Stevens…if anything goes wrong’

“Sir”

‘It’s all on you!’

“Understood sir.”

‘Alright then… bring them in….and Stevens…find out who instigated this fiasco. Dismissed!’

“Sir!”

What was also made clear to Sgt Stevens was that the WDs stay was temporary. They were to be put on the train back to Halifax the very next day. It didn’t work out that way though. Little did they know, there was no return passenger train scheduled until that Sunday. Was this simple bad luck or was it planned? That too shall never be known. In the meantime, F/L Monasch simply had no choice but to contend with an unusual and unwanted presence until then.

F/L Monasch hurriedly made arrangements to accommodate the 12 WDs. Sleeping quarters were arranged in the Administration building. Monasch assigned men to remove the office equipment and files from the administration room. It was ready by the time the WDs arrived late one Friday night around 11pm.

Mickey Stevens photograph – Archives of Mary Richard with permission

Monasch’s worst fears never materialized. The following day, the usual boredom of station life was replaced by actual face-to-face conversations. Men and young women of the same own age and service simply mingled, shared some laughs, and had a good time.

It was a much welcomed break from discipline and routine. For one small moment they could forget the war and enjoy the company of one another as young people sharing a moment of card games and volley ball. It was a most joyful respite from the regular and the mundane routine.

The women too appeared to be enjoying themselves immensely. Why not? They were treated like royalty. They were waited on hand and foot. There was no lack of hospitality.

But after two days of fun, the WDs were once again driven back over the long bumpy road back to the railway station. They returned safely and on time to Halifax, where they once again resumed their duties at the filter centre. But enjoyable or not, such a visit was never to be repeated again.

Mickey Stevens photograph – Archives of Mary Richard with permission

The Fall out

The WD visit was over and it was a big success. All that was left was speculation in the aftermath of “whodunit?”

Part of the speculation was why there was no return visit? Sgt Stevens suspected that the only reason why there was never a return “escapade” was the thought of another journey on the back of our transport truck over rough roads. It was an intrepid journey over some 60 miles of rough travel, with no pit stops that likely kept them away. It may have been the day long train ride from Halifax to Monastery as well. Surprisingly too, F/L Monasch never issued any order prohibiting a repeat visit but, he did not say whether he would allow one either.

Sgt Stevens thought it was all over now that the WDs had departed. He was soon proven wrong on that account. There was fallout. The CO still wanted to know who was responsible. So Sgt Mickey Stevens embarked on rounding up the “usual suspects”.

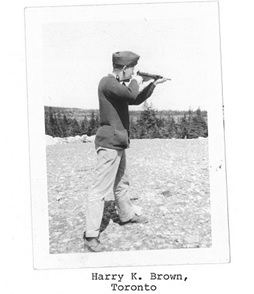

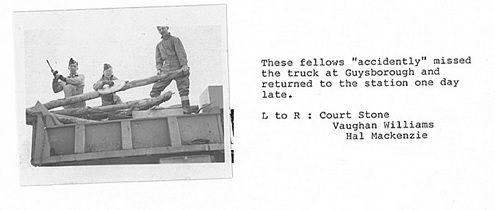

Mary Richard Archives with permission

Sgt Steven’s hit list was very small. There were only 9 among the unit who had access to the phones and radios. They were the radar men. There were three probable principal in Steven’s mind. Quite high on his hit list were radar operators Gordon Chisholm, of Toronto and Bill King, of Victoria. But these two had air tight alibis. Both Chisolm and King were at Monastery railway station on the day. They were off on passes and were at the station when the train arrived with the WDs. Stevens suspected that they knew what was happening and were only leaving the area before “shit hit the fan”. Steven’s had little hope of pinning the blame on them.

His third and final suspect was radar operator, Al Snow of Montreal. Snow was noted by his was most conspicuous absence at certain times throughout the visit. But having suspicions and finding proof were entirely different matters.

It was only later that he learned of Monasch’s true reason for wanting to know who the culprit was. Monasch realized that the visit actually had been handled rather well. More importantly, he had not been left with any problems. In fact station morale was vastly improved by the undertaking. Monasch no longer wanted to reprimand the guilty party, all he wanted to know was who had so much moxie to do it in the first place!

In the end the matter quietly was dropped. The incident of the uninvited WDs passed. The story now resides in the pantheon of station legend. But it did have one intended or unintended consequence. One Norma Stevenson, WD met one radar operator Marvin Miller. They later married.

Mickey Stevens photograph – Archives of Mary Richard with permission

“It’s the most wonderful time of the year…”

Every serviceman looks forward to holidays with certain nostalgia and a longing to be home with family friend and loved ones. The most treasured times of the year are Christmas and New Year’s. But there was never any guarantee that you’d be home for the holidays. You usually just made do, at the unit, with the people that you served with. They were after all, your extended family.

It was a very lucky airmen indeed who managed to wangle some hard-earned and well-deserved leave to be home for the holidays. Sometimes it was a matter of luck of the draw. The CO simply couldn’t let everyone skive off for the holidays. He still had a station to run, a job to do, and a war to fight.

Some were lucky to get home for the holidays. For the rest of the station, the holidays were spent together. One of a CO’s prime jobs was looking after the welfare of his men. That task was often made simpler by military traditions that helped there too! But engaging a popular tradition depended on where you were and what was happening too.

Hopefully circumstances would allow the arrangement of a “Men’s Christmas Dinner” or a “New Year’s Levy” even if the scale was simply reduced to making sure that you had a traditional turkey dinner, boiled sweets and plenty of liquid refreshment to enjoy. Sometimes it was the few hours or minutes stood down that were most appreciated while each man or women took their turn to eat and enjoy the day.

The war must have been long and hard for the men at No 5 Radar Unit where the separation from family and friend was deeply felt especially at the festive season. F/Lt Monasch made a special effort both for him and his men that festive season of 1944/45. New Year’s Eve 1945 would be a celebration that would be spent with family, but not away at “home” but one spent with them at No 5 Radar Unit.

A number of wives made their way to Cole harbour that Christmas and New Year’s. They were special guests at the New Year’s celebrations at the station that year. F/Lt Monasch’s wife and son were amongst the guests. This was a special occasion. The mess was decorated with wreaths, branches and other festive decorations. The room was uncharacteristically warm and bright. It was spotless.

All was prepared and made ready for the arrival of family and guests from Cole Harbour and the surrounding area. It would be a New Year’s to be remembered. It was 1945, a year that would see dramatic change, trials, hope and promise.

The time came and everyone sat in and pictures taken to mark the occasion. It wasn’t very formal. The tables were set up in a hollow square and every one gathered round. There was no fine china or crystal glassware. The table was set with the coarse tableware and glassware used every day. The table cloths were the cleanest sheets from the laundry set upon the tables.

The fixings of the celebration were simple; apples, beer, food and sweets set about for all to enjoy. It truly was a family gathering and an occasion certainly most memorable to F/Lt Monash and his family. It was also a time where his men probably saw him for what he was, a family man and a human being after all! But there was a certain solemnity and sadness in the air in the group photograph taken that day to mark the occasion.

The Festive Season of 1944/1945 was supposed to be a happy one. No 5 Radar unit had a challenging year. They worked hard and diligently at their post. One lucky group of airmen was reward with well-deserved leave for the effort! Leave to go home and spend Christmas and New Year’s with their families.

There was no certainty on who would get leave or when. But once told for those selected that year, their excitement would build day by day until the lucky few departed. Their mood would certainly have been a festive one. That day came when an intrepid group set out for home on 20 December that Christmas in 1944.

They posed for a parting shot. Mickey Stevens was amongst them. He unfortunately was one of those who had to stay in Cole Harbour that year.

Despite their joy there was a trial getting out of the station. The trouble began 19 December 19441. The morning of 19th started out well. The Stake truck proceeded out on a routine administration run. It wasn’t due back until that evening.

The weather became overcast during the day that turned into a raging blizzard that evening. The boys were looking forward to the trucks return. There was no movie put on that night. The movie that they had and could not be shown because of the poor condition of film. So they waited in anticipation of the stake trucks return.

After struggling for 2 1/2 hours to go 16 miles through 4 foot drifts, the stake truck driver gave up the ghost an elected to stay at a farmhouse approximately 19 miles from Station that night. No mail was received that night due to storm. More importantly the means out was stuck in the snow until it could be dug out!

The 20 Dec 44 turned out to be a regular day. The weather had cleared but roads were badly snowed in. A panel truck was going to Queensport with a group of men with shovels to clear road so they could get the stake truck in. It would seem that our intrepid travellers had no choice but to walk out on the Barrens if they ever wanted to get home in time for Christmas!

Arrangements were made to pick them up at Queensport. An Army Transport Unit would be dispatched to take them to the train station. The station’s panel truck finally returned to station with its rations and work crew at approximately 4PM. The Stake Truck was still stuck in the snow, all too late for the group to use.

The men who walked out to Queensport were finally picked up by the Army truck for their final leg to the train station. It turned out to be an eventful journey. The roads were in bad shape.

No 5 Radar Unit received a horrific call at approximately 8PM that night. They were informed that the Army truck had been involved in an accident, that there had been RCAF casualties. The Army Truck had come to harm in Half Way Cove, about 25 miles from station.

The number of RCAF personnel, who were passengers in the truck were first listed as injured. A later report modified and updated the initial report. Sadly R282593 LAC Flower, EJ had been killed. The others condition was listed as injured, suffering shock. All were expected to live. It was a sad Christmas. The next of kin were soon advised.

An inquest was held immediately after accident. The inquest found Ed Flower’s death to be accidental. No 5 Radar Unit formed a “Committee of Adjustment”. It had the unpleasant task of gathering and cataloguing Ed’s belongings. They also had the sad duty of selecting an escort to accompany Ed’s body back to his family.

Monasch’s ordeal had just begun though. He proceeded to Antigonish on 21 Dec 44. The weather was again good but cold. His was a sombre journey that day. Monasch made the necessary funeral and transportation arrangements in Antigonish. He obtained Flower’s death certificate and burial permit.

Monasch had the other airmen to attend to as well. They were at St. Martha’s Hospital in Antigonish for a complete examination. Each man had been examined by Dr. McKinnon. They were lucky Dr. McKinnon released them all. They only suffered shock.

Monasch’s job still wasn’t over. There was some administration outstanding. Monasch had to inform the Senior Medical Officer at Sydney of the death of an airman. He also contacted the RCASC Depot in Sydney. He needed a wrecker to get his Unit’s 4 X 4 truck back to Cole Harbour. The 4×4 was still stuck fast in the snow. It was simply one thing after another for F/Lt Monasch that day.

Ed Flower’s body began his final journey to his family on 22 Dec 44. The weather that day was good but it continued to being extremely cold. LAC Flower’s remains were shipped to Toronto under the escort of LAC Chisholm also of Toronto, a very sad duty.

There was a blanket of gloom surrounding the Unit. A movie that night of the repatriation of the body helped to raise their spirits. But it wasn’t long until the gloom was brought back to them. Canadian Press phoned F/Lt Monasch who was asked to make a statement on the death of LAC Flower. It was a untimely reminder of what happened.

Ed Flower was only 29 years old at the time of his death. His passing was deeply felt by his father Frederick and mother, Maude Jean Flower of Toronto. Ed was simply going home for Christmas, the most wonderful time of the year. It would be the saddest Christmas of all.

Ed’s passing at what was supposed to be the most joyous time of year was deeply felt by his military family too. There was hole in the fabric of life greatly felt amongst the small and tight group of men who lived as one on a small station. But it must have been the saddest Christmas for his wife, Edna M. Flower, of Toronto. Edna lost a loving husband.

The Difference Between Revenge and Justice Served!

No 5 Radar unit was generally a very well disciplined unit. There were very few occasions where its commanding officers had to exact military justice. The guardhouse jail was most under-utilized facility on the station. There were very few infractions and occupants that eventually it was converted to be used as a chicken coop!

There were a few times when the chickens were evicted and the cells utilized for the intended purpose. Most of the Unit’s infraction though were of a minor disciplinary nature. It wasn’t worth the effort to open the cells. But justice had to be seen to be done. Discipline and military order after all had to be maintained. So the CO’s justice would often amount to extra duties and added duty watches.

But sometimes it was much more serious. What to do about a “hijacking”. Yes there was a hijacking of sorts that involved Morris Rachlis of “pickled herring” fame. Morris and several airmen were picked up at the train station by the ration truck. They were returning from leave. The driver of the truck was notoriously bad. The group got as far as Guysborough where a coffee break was always taken.

The group expressed their concerns to the driver. They lambasted his bad driving habits while on the paved road from Monastery to Guysborough that was on the smoothest and safest part of their journey. It was obvious that their complaints and issues were falling on deaf ears.

Morris decided to take matters in hand and bodily removed the driver from the truck and threw him the back with his comrades. He then drove the group to the station where upon arrival the driver laid a charge before the CO of unauthorized use of a military vehicle.

The CO was in a pickle. What to do? He had heard several complaints about the safety of this driver. And if the CO was F/Lt Monasch, the recent events of Christmas 1944 may have swayed his decision and what justice was meted. Morris Rachlis was given a reprimand. The reprimand satisfied the sensibilities of all.

Some matters were easily resolved and brushed under the carpet if you will. Still others demanded more severe reaction and response. This was especially the case when those matters gained the personal interest of a superior headquarters.